Back to The EDiT Journal

Governance Over Gigabytes: Why ASEAN's Education Future Depends on Politics, Not Just Platforms

Research and analysis from Suresh S Kartigaysu and the EDT&Partners APAC team on education reform across ASEAN.

Policy & Funding

Digital Transformation

Governments

EdTech

In this article

The Three Governance Lenses

From Bedrock to Breakthrough: The Reform Sequence

The Implementation Deficit

What This Means for Stakeholders

This article is the second piece in a two-part series on governance and education reform in ASEAN. These insights were first shared at the Singapore Education Lounge in November 2025, hosted by AWS, EDT&Partners, and the Singapore Education Network (SEN).

You can read Part 1, From Framework to Practice: What Happens When Governance Meets the Ground, a synthesis of the panel discussion on building trusted education systems across ASEAN, here.

Analysing education reform across nine ASEAN countries revealed an insight that challenges conventional wisdom: resource gaps, connectivity, devices, funding are not the primary barriers to building future-ready classrooms. The real barrier is political.

Across Southeast Asia, from Jakarta to Vientiane, a consistent pattern emerged: countries with strong governance capacity achieved more with less, whilst those with abundant resources but weak institutions struggled to translate investments into outcomes. Vietnam spends significantly less per student than Thailand but consistently outperforms it in learning outcomes. Singapore and Brunei share oil wealth and high per-capita spending, yet one is a global education leader whilst the other proceeds cautiously, constrained by ideological frameworks. The difference isn't money or technology, it's governance.

The Three Governance Lenses

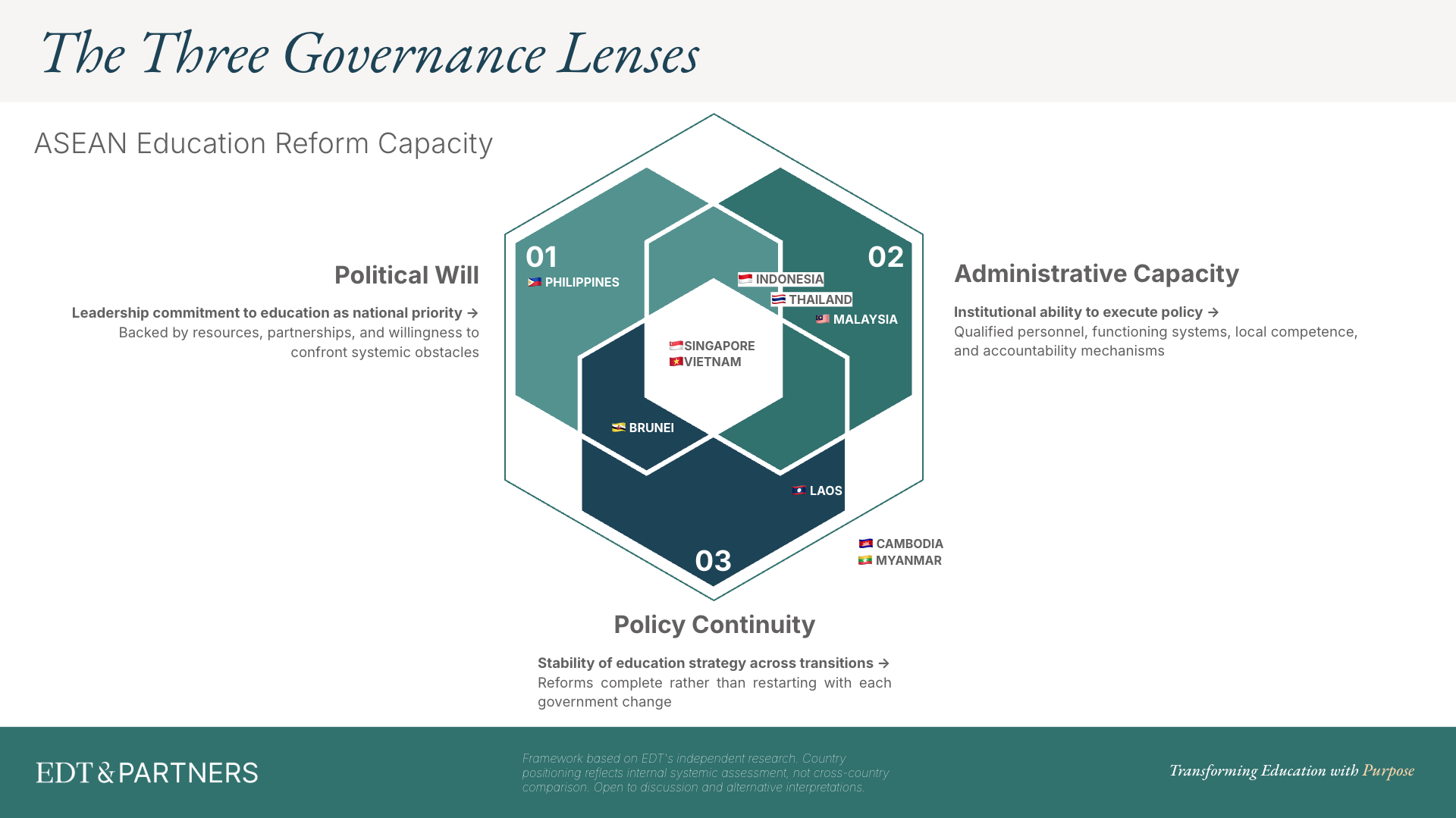

Our research identified three dimensions that determine whether education reform succeeds or stalls (Fig. 1): political will, administrative capacity, and policy continuity. Political will means leadership genuinely prioritises education with resources and resolve to tackle entrenched obstacles like corruption or patronage. Administrative capacity is the institutional ability to execute, qualified civil servants, functioning procurement systems, data infrastructure, local competence. Policy continuity ensures reforms survive leadership transitions rather than restarting with each new government.

Vietnam sits at the intersection of all three: one-party consistency provides continuity, economic strategy drives political will, and a disciplined bureaucracy delivers capacity. This alignment explains its exceptional performance. Most ASEAN countries have one or two dimensions but lack the third. Malaysia has capable systems but policy reversals every election cycle. Thailand has bureaucratic competence but political instability disrupts continuity. Indonesia and the Philippines have constitutional mandates for education and political will on paper but weak local capacity fragments implementation. Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar lack most dimensions entirely, with Myanmar's post-coup collapse representing complete system breakdown.

From Bedrock to Breakthrough: The Reform Sequence

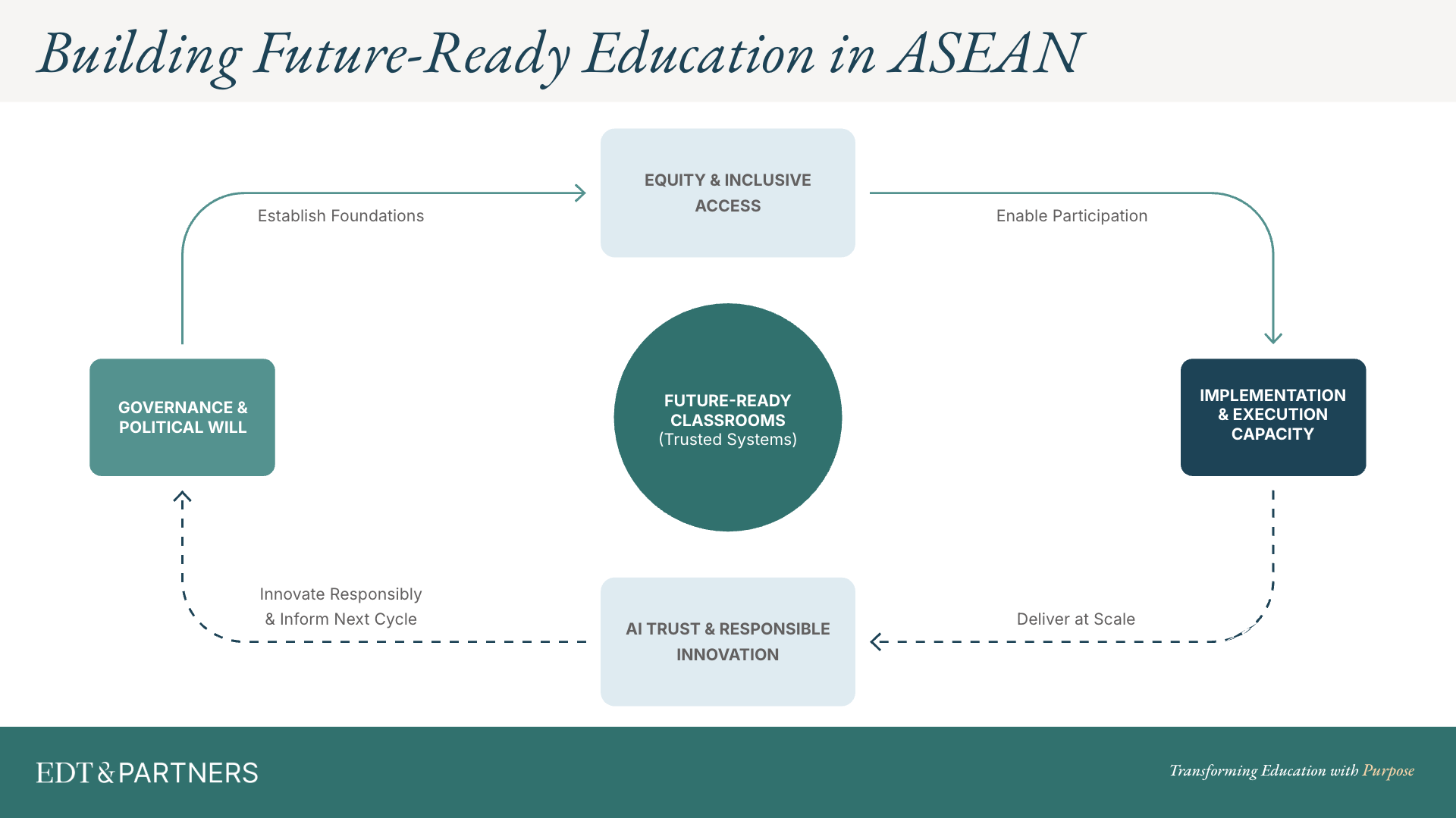

What became clear is that these elements aren't independent, they're sequential and interdependent (Fig. 2). Governance acts as bedrock, establishing foundations for everything else. Without stable institutions and sustained political commitment, equity initiatives struggle to take root. Connectivity reaches rural areas and teachers receive training only when governance creates enabling conditions.

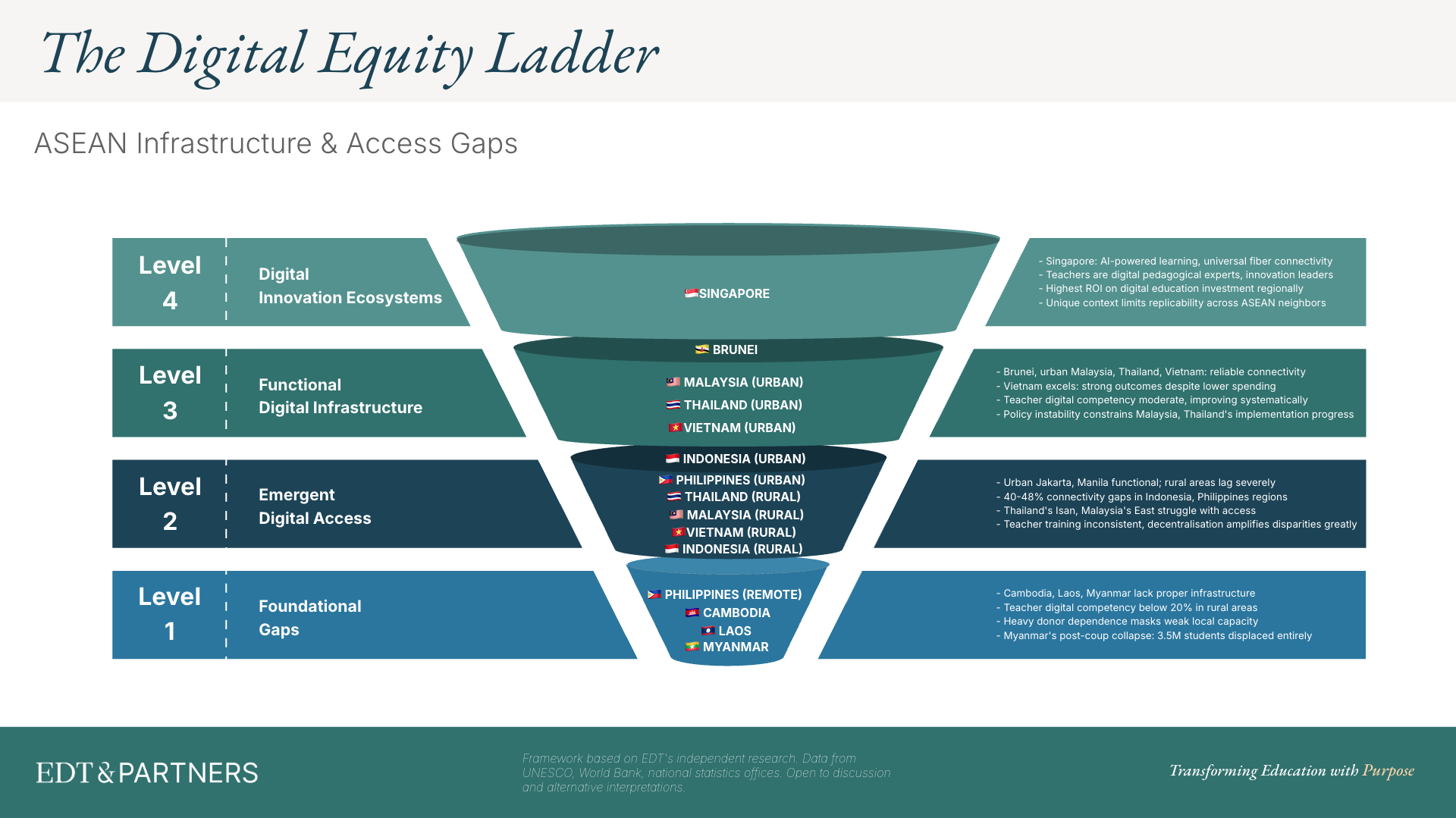

Equity, in turn, enables implementation. Systematic execution depends on equitable access policies actually reaching classrooms rather than stalling at ministry headquarters. As demonstrated in our Digital Equity Ladder analysis (Fig. 3), within-country gaps often exceed between-country disparities. Urban Jakarta and rural Papua exist on different rungs of infrastructure readiness, despite sharing the same national policy environment.

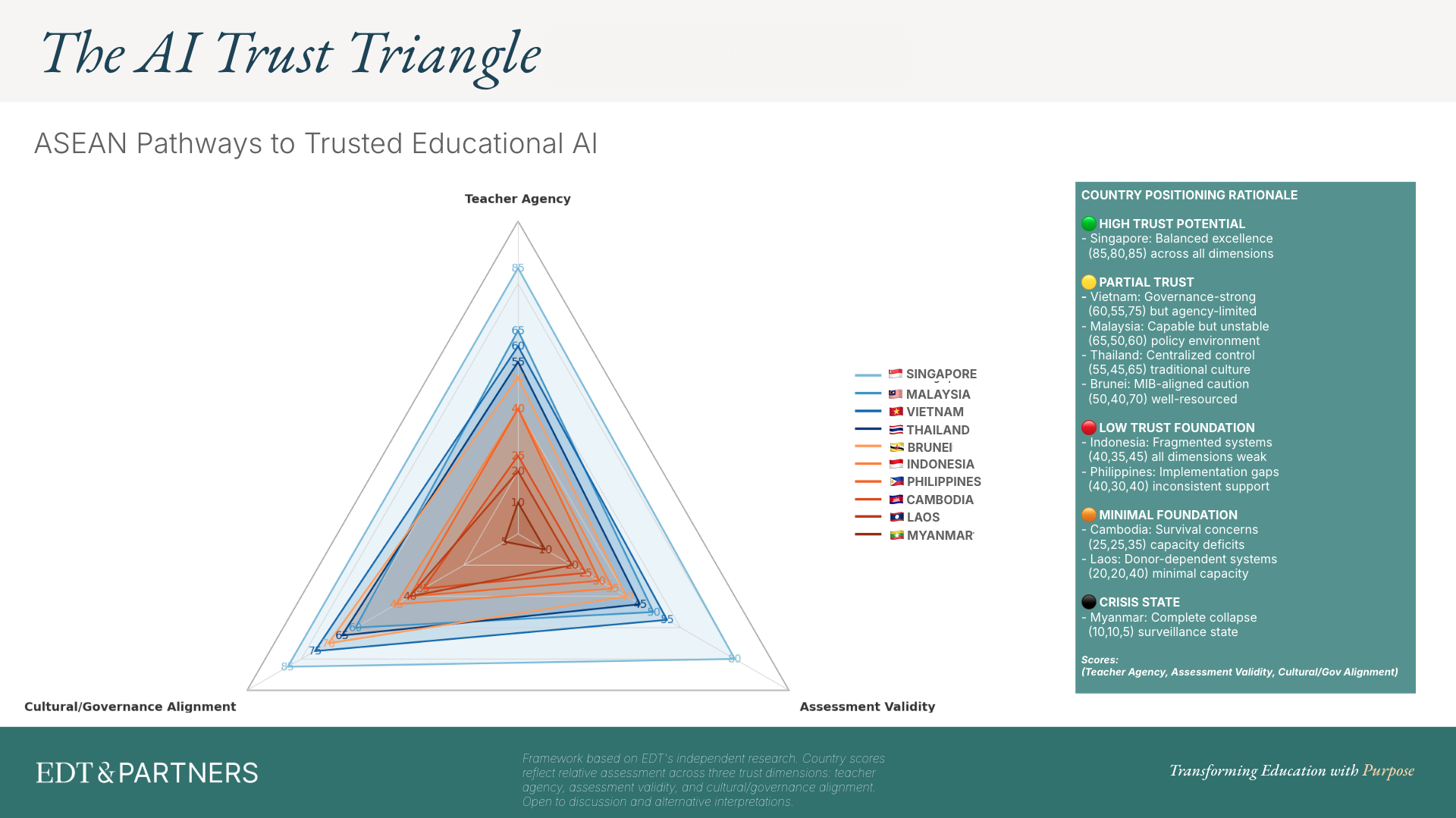

Effective implementation then creates conditions for AI trust and responsible innovation. When teachers see systems work consistently, when students benefit reliably, trust builds. Our AI Trust Triangle framework (Fig. 4) shows that successful technology adoption requires balanced strength across teacher agency, assessment validity, and cultural-governance alignment. Trust allows responsible innovation not as a leap of faith, but as a logical next step informed by demonstrated capacity.

The outcome is future-ready classrooms: trusted education systems serving all students with quality, equity, and appropriate technology. Critically, classroom outcomes feed back to governance, informing next priorities and creating a continuous improvement cycle.

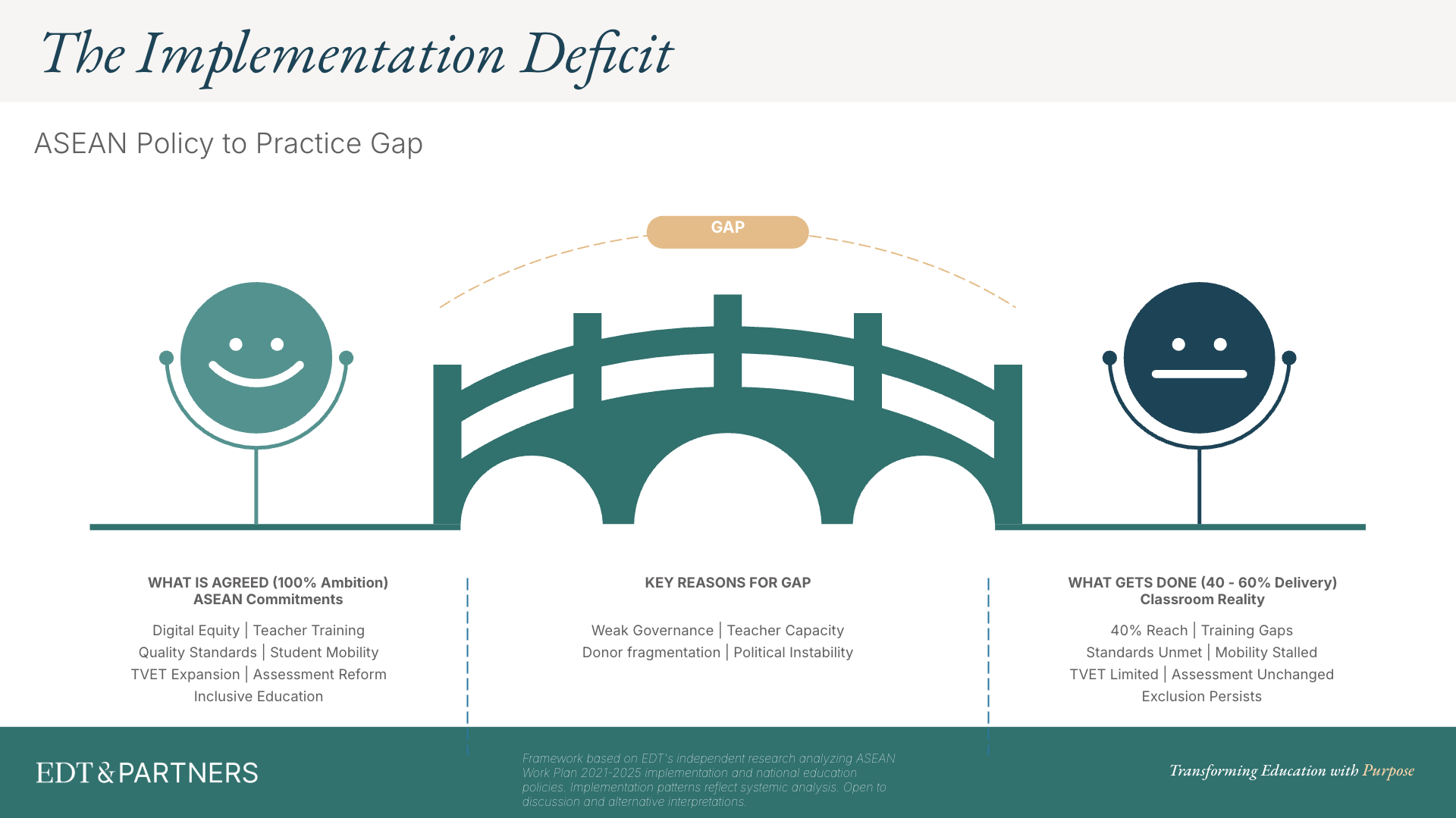

The Implementation Deficit

Here's the sobering reality: 40-60% of ASEAN's education commitments never reach students (Fig. 5). The ASEAN Work Plan 2021-2025 promises digital equity, teacher training, quality standards, student mobility, TVET expansion, assessment reform, and inclusive education. On paper, 100% ambition. In practice, 40-60% delivery. The gap isn't aspiration, it's execution capacity.

Skip a step in the sequence, pursue AI adoption without ensuring equity, implement reforms without governance capacity and the cycle breaks. Address all stages systematically, and reform becomes sustainable. This is what separates Vietnam's trajectory from Cambodia's challenges, Singapore's excellence from Myanmar's collapse.

What This Means for Stakeholders

For policymakers: Prioritise governance reforms before technology procurement. Establish transparent budget tracking, strengthen local administrative capacity, and create mechanisms for policy continuity across leadership transitions. Technology investments yield returns only when institutions can implement and sustain them.

For EdTech companies: Conduct governance readiness assessments before market entry. The most sophisticated platform fails in contexts lacking implementation capacity or teacher readiness. Design for contexts, not just capabilities, consider offline functionality, mother-tongue support, and integration with existing (often fragmented) systems. Success requires partnership with local capacity-building, not just product deployment.

For international donors and development partners: Align funding with national education frameworks rather than introducing parallel systems. Coordinate amongst yourselves to prevent fragmentation. Five donors supporting five different platforms in one country compound rather than solve the coordination problem. Support governance capacity-building as a precondition for programmatic success.

For educators and institutional leaders: Advocate for the governance conditions that allow professional expertise to flourish. Demand transparent resource allocation, systematic professional development, and decision- making authority appropriate to your proximity to students. Participate in peer learning networks across ASEAN to share implementation strategies that work despite challenging governance contexts.

The path to future-ready education in ASEAN isn't paved with devices and connectivity alone, it's built on governance foundations that enable equity, which powers implementation, which earns trust for innovation. Get the sequence right, and transformation becomes possible. Get it wrong, and even the best technology remains trapped in the implementation deficit, another ambitious plan that never reached a single classroom.

.png)

.jpg)