Back to The EDiT Journal

From Framework to Practice: What Happens When Governance Meets the Ground

Insights from the Singapore Education Lounge panel discussion on building trusted education systems across ASEAN

Policy & Funding

Digital Transformation

Governments

EdTech

Schools & Universities

In this article

Governance: Designing for Transitions

Equity: Infrastructure as Enabler, Not Solution

AI Trust: Cultural Context and Teacher Agency

Implementation: Where Vision Meets Variance

What Practitioners Revealed

From Dialogue to Direction

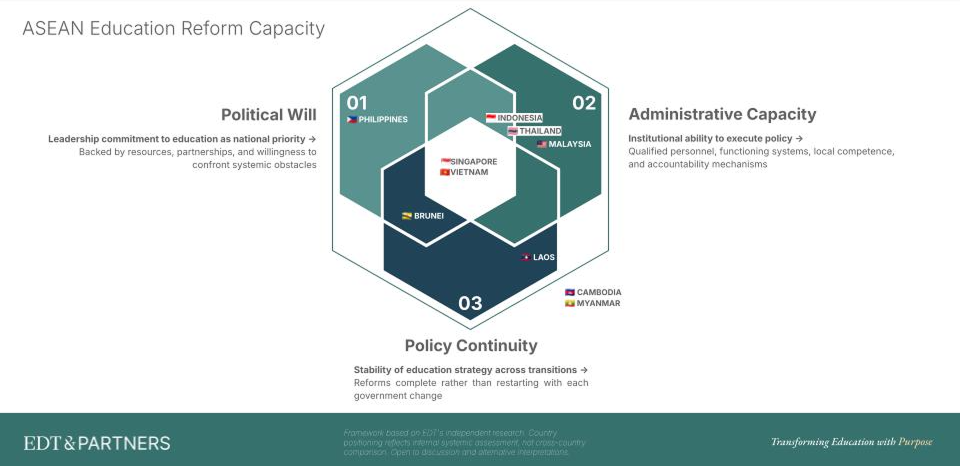

When research meets practitioners, theory gets tested. At the November 2025 Singapore Education Lounge, hosted by AWS, EDT&Partners, and the Singapore Education Network, four panelists brought decades of implementation experience to bear on EDT&Partners' ASEAN education reform research. What emerged wasn't validation or refutation, but nuance: the messy, complex reality of translating governance frameworks into classroom outcomes.

The panel brought together Jenn-En from GovTech Singapore, Phway Pann from AWS, Alessandro Cattani from Seesaw, and Ryan Lufkin from Instructure. Each operates at different altitudes: government infrastructure, cloud services, K-12 platforms, and higher education systems. Yet their responses revealed striking convergence on where reform succeeds and where it fractures.

Governance: Designing for Transitions

The research positioned governance as bedrock. Jenn-En grounded this in Singapore's experience: "Understanding the core intent of education is crucial for sustaining policies across leadership changes”. GovTech designs digital infrastructure not for a particular minister's vision, but for the educational mission that persists regardless of who occupies the office. This isn't merely technical architecture; it's political architecture, anchoring systems to outcomes rather than administrative preferences.

Ryan Lufkin noted that Canvas' "open architecture allows for easy integration with various tools and supports diverse educational standards", but acknowledged the tension between platform openness and national requirements for curriculum alignment. Vietnam manages this through centralised discipline; Singapore through intentional design. The question for countries lacking either is whether technology can compensate for governance gaps. The panel's implicit answer: no, but thoughtfully designed platforms can reduce the capacity threshold required whilst institutions strengthen.

Equity: Infrastructure as Enabler, Not Solution

Phway Pann illustrated the Digital Equity Ladder framework through Sekolah.mu, serving over 10 million Indonesian students: "Innovative solutions tailored to local contexts are essential for reaching underserved communities”. Yet "tailored" means confronting hard truths. Jenn-En described providing archived Wikipedia to village schools via hard disks, no connectivity required.

Alessandro Cattani acknowledged Seesaw's flexibility in helping "teachers adapt their teaching methods whilst still aligning with centralised curricula”, but noted the platform assumes baseline device access. The equity challenge isn't just reaching remote areas; it's serving mixed-capacity environments where urban institutions connect seamlessly whilst rural ones struggle with basics.

The insight from Alessandro's discussion of Universal Design for Learning: equity isn't uniformity. A Metro Manila classroom and a Lao village school need different tools, different pedagogies, different success measures. Equity means both can achieve context-appropriate learning outcomes.

AI Trust: Cultural Context and Teacher Agency

The AI Trust Triangle framework posits that trust emerges from balanced strength across teacher agency, assessment validity, and cultural-governance alignment. Alessandro addressed this directly: "Seesaw prioritises teacher-facing AI tools, such as an AI translator and chat prompts for lesson planning, to support educators in personalising learning experiences”. The design choice reflects developmental appropriateness: AI for teachers, not students, in early education.

But trust isn't just technical safeguards; it's cultural fit. Bruneian MIB frameworks, Malaysian Islamic educational considerations, and Vietnamese ideological requirements aren't obstacles to work around. They're contexts to design for.

Ryan highlighted the assessment crisis: traditional exams lose reliability when students access generative AI. Canvas is evolving frameworks "to measure genuine understanding rather than content reproduction", but evolution requires institutional permission. Convincing examination boards across ASEAN to embrace portfolio assessments when many still use paper-based memorisation tests remains challenging.

Jenn-En provided Singapore's answer: proactive governance through mandatory AI training for public servants and open-source tools like AI Verify for responsible adoption. But this demonstrates governance capacity enabling innovation, the very bedrock the research identifies as a prerequisite. Countries lacking this capacity face a bind: they need AI literacy to navigate AI risks, but lack institutional mechanisms to build that literacy systematically.

Implementation: Where Vision Meets Variance

The Implementation Deficit framework documents a 40-60% gap between ASEAN commitments and classroom delivery. The panel didn't dispute the gap; they explained it.

Ryan identified change management in institutions as critical. Alessandro emphasised that professional development training determines whether adoption succeeds or fails. But professional development assumes teachers have time, institutional support, and psychological safety to learn. Phway Pann's peer-learning mechanisms (study trips and workshops) reach only a fraction of ASEAN's teaching force. The implementation deficit isn't a mystery; it's mathematics. Vietnam's disciplined bureaucracy cascades training systematically; Cambodia's fragmented system cannot.

Jenn-En highlighted coordination challenges, noting Singapore's whole-of-government approach assumes ministerial coordination, a governance capacity many ASEAN members lack. Without it, initiatives fragment. Different donors push different systems, governments cherry-pick projects without unified strategy, and the deficit persists.

What Practitioners Revealed

The panel surfaced three truths that nuance the research. First, timelines matter. Frameworks present sequences (governance enables equity enables implementation enables trust), but transformation measures in years, not quarters. EdTech funding cycles rarely align with governance capacity-building timelines.

Second, failure modes are specific. The Implementation Deficit aggregates, but implementation fails in granular, fixable ways. Generalised capacity-building helps less than targeted problem-solving.

Third, hybrid solutions are the norm. Reality is messier than ideal types. ASEAN education systems are all hybrid, all improvising, all adapting. Frameworks demanding purity fail.

From Dialogue to Direction

What emerged is a practitioner's framework layered atop research: governance capacity determines whether equity initiatives root, but equity progress also builds governance legitimacy, creating virtuous cycles when conditions align. Technology platforms can't create governance capacity, but thoughtful design can reduce the capacity threshold required for basic functionality, buying time for institutions to strengthen.

The path forward isn't choosing between governance reform and technology adoption; it's sequencing them intelligently and accepting that perfect conditions never arrive. Start where you are, build what you can, learn from failures, and feed those lessons into the next cycle. As Jenn-En noted, synchronisation between technology and policy isn't achieved once; it's maintained continuously. The reform cycle isn't a project plan; it's an operating model. ASEAN's education future depends on treating it as such.

View the complete research frameworks by EDT&Partners in the upcoming article: "Governance Over Gigabytes: Why ASEAN's Education Future Depends on Politics, Not Just Platforms"

.png)